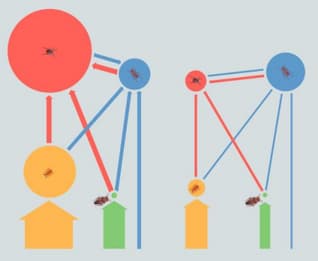

The diagrams here show energy flows between trophic groups of animals in a natural rainforest (left) and an oil palm plantation (right). The animal groups are primary consumers (green), detritivores (yellow), carnivores (red) and omnivores (blue). The size of the circles indicates the biomass of the groups of animals and the width of the arrows indicates the amount of energy flowing from one group to another.

State the reason for the much lower biomass of carnivores in the oil plantation than in the natural rainforest.

Important Questions on Energy

The diagrams here show energy flows between trophic groups of animals in a natural rainforest (left) and an oil palm plantation (right). The animal groups are primary consumers (green), detritivores (yellow), carnivores (red) and omnivores (blue). The size of the circles indicates the biomass of the groups of animals and the width of the arrows indicates the amount of energy flowing from one group to another.

Suggest a reason for a higher biomass of omnivores in the oil palm plantation than the natural rainforest.

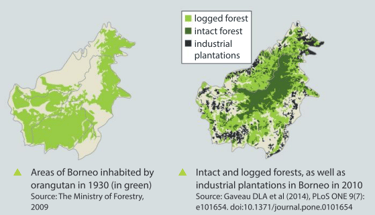

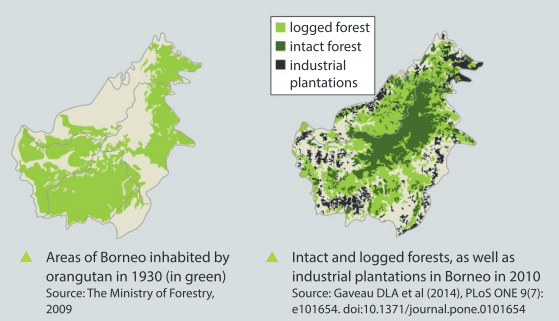

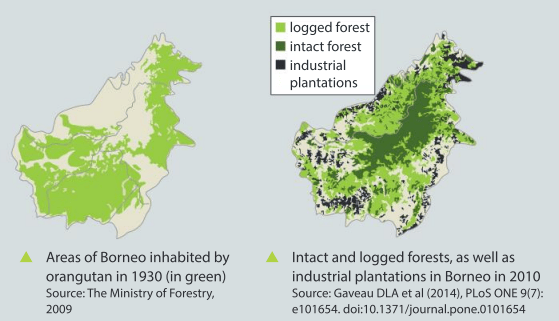

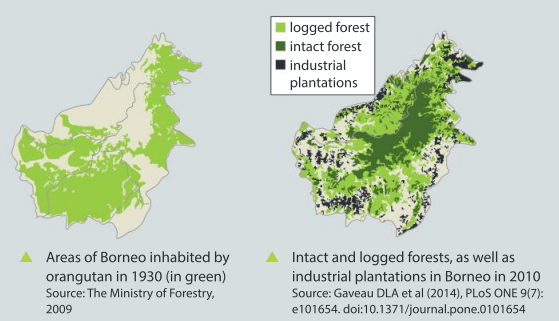

One hundred years ago, there was probably more than 230,000 Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) in their natural tropical rainforest habitats on Borneo and Sumatra. Population estimates by the World Wide Fund for Nature in 2016 were 41,000 on Borneo and 7,500 on Sumatra. The maps here show the parts of Borneo that orangutan inhabited in 1930 and the parts of the island where there was natural intact forest, logged forest, and plantations of rubber trees and oil palms in 2010.

Analyse the information in the maps to assess whether or not:

Orangutan originally inhabited all areas of forest on Borneo.

One hundred years ago, there was probably more than 230,000 Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) in their natural tropical rainforest habitats on Borneo and Sumatra. Population estimates by the World Wide Fund for Nature in 2016 were 41,000 on Borneo and 7,500 on Sumatra. The maps here show the parts of Borneo that orangutan inhabited in 1930 and the parts of the island where there was natural intact forest, logged forest, and plantations of rubber trees and oil palms in 2010.

Analyse the information in the maps to assess whether or not:

plantations of rubber or palm oil have been established in areas formerly inhabited by orangutan.

One hundred years ago, there was probably more than 230,000 Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) in their natural tropical rainforest habitats on Borneo and Sumatra. Population estimates by the World Wide Fund for Nature in 2016 were 41,000 on Borneo and 7,500 on Sumatra. The maps here show the parts of Borneo that orangutan inhabited in 1930 and the parts of the island where there was natural intact forest, logged forest, and plantations of rubber trees and oil palms in 2010.

Analyse the information in the maps to assess whether or not:

Areas of intact forest remain where orangutan were living in 1930.

One hundred years ago, there was probably more than 230,000 Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) in their natural tropical rainforest habitats on Borneo and Sumatra. Population estimates by the World Wide Fund for Nature in 2016 were 41,000 on Borneo and 7,500 on Sumatra. The maps here show the parts of Borneo that orangutan inhabited in 1930 and the parts of the island where there was natural intact forest, logged forest, and plantations of rubber trees and oil palms in 2010.

Discuss whether logging or clearance of forest for plantations has had more harmful effects on the orangutan.

| Oil crop | Average oil yield (kg ha-1year-1) | Planted area (million hectares) |

| Soybean | 400 | 94.15 |

| Sunflower | 460 | 23.91 |

| Rapeseed(canola) | 680 | 27.22 |

| Oil palm | 3620 | 10.55 |

If you happen to mention palm oil to most people outside of Asia you are unlikely to get a particularly positive reaction. Over recent years, media coverage of palm oil has typically included images of displaced orangutan and burning, degraded tropical forests. There has been a feeling that palm oil is an evil that needs to be stopped. Indeed, in some richer countries, there have been attempts to organize consumer boycotts of palm oil products. Tanging from cosmetics to chocolate. Examples include France, the United Kingdom and Australia. But there is another story about palm oil that is much less frequently heard, especially in richer countries. This is a story about an ancient and bountiful African tree whose fruits provide a wholesome, vitamin-rich oil that feeds 2 billion to 3 billion people in 150 countries every day.

The oil palm tree has been cultivated as a source of food and fibre by people in western Africa for as much as 4,000 years and was harvested by our hunter-gatherer ancestor for tens of millennia. Palm oil is a uniquely productive crop. On a per-hectare basis, oil palm trees are 6—10 times more efficient at producing oil than temperate oilseed crops such as rapeseed (canola), soybean, olive and sunflower. The trees also have a productive life of around 30 years. Soil in oil palm plantations is rich in organic content and is less disrupted compared to temperate, annual oil crops where highly destructive annual ploughing of the soil is required.

In 2014, the total estimated global production of palm oil was almost 70 million tonnes (Mt). Over 85% is exported from Indonesia and Malaysia, mostly to India and China, where the fruit oil is used in food, including as a cooking or salad oil, and in a wide range of processed food products. If oilseed crops were to replace palm oil, it would require at least 50 million additional hectares of prime farmland just to produce the same amount of edible oil. The seed oil from palm is rich in lauric acid, a critical component in many cosmetics and cleaning products. Much of this type of palm oil is exported to Europe where it is used

in toothpaste, washing up liquids, shower gels and laundry detergents. The only viable alternative oil that is rich in lauric acid comes from coconut, but the oil yield of this plant is less than 10% of palm oil. To completely substitute coconut for palm oil would require cultivating ten times as much tropical land.

This is rarely realized by consumers who choose to use products coconut oil instead of palm oil.

Another misconception is that palm oil is overwhelmingly a "big business" crop. In fact, there are about 3 million smallholder growers, nearly all of whom farm individual family-owned plots. In Indonesia, which is the largest palm oil-producing country, smallholder plots account for of the total crop area. I have recently returned from a fact-finding visit to Sarawak where we saw some of the innovative ways that local people are growing oil palm alongside other crops. Over the past year or so the pendulum of informed opinion has started to swing away from a simplistic view of palm oil as an unmitigated environmental scourge and towards a more nuanced approach that recognizes the genuine pros and cons of this bountiful tropical crop. One of the most encouraging developments has been the establishment of a reasonably robust and independent body to certify the environmental and social credentials of palm oil. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, or RSPO, has a vision to "transform the markets by making sustainable palm oil the norm". The RSPO has over 2,000 members globally that represent 40% of the palm oil industry, covering all sectors of the supply chain.

There is also an increasingly active international research effort aimed at understanding the ecological and environmental impact of oil palm compared to other habitats such as rainforests and rapeseed or soybean farms. One example of this research is a recent analysis of tropical peat soils, some of which have been targeted for oil palm cultivation. When improperly farmed these soils can release large amounts of CO2 and grow poor crops. But the analysis found some of the types of peat can readily support oil palm crops without high CO2 emissions, while others should bc left un-farmed and conserved. They conclude that rather than a blanket-ban on farming peat soils, decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis depending on the type of peat. Another study did a more rigorous life cycle assessment of oil crops, which is a measure of their overall environmental impact and found the overall ecological impact of palm oil is comparable, and sometimes superior to temperate crops. Two other studies examine the potential impact of land use and climate change on biodiversity in Borneo where a great deal of oil palm planting has occurred. The conclusions include the need to establish nature reserves in upland areas where climate change will be less severe and to improve connections between reserves and plantations with wildlife corridors.

There are undoubtedly many significant challenges facing oil palm, and further encroachment onto sensitive native forest areas should be minimized and eventually halted. But palm oil is also a uniquely efficient edible crop that is essential for food security in Africa and Asia. By working together as an international community that includes scientists, farmers, processors and consumers we aim to develop solutions to many of the problems faced by oil palm. Hopefully, this will soon enable palm oil to regain its rightful place as one of the stars in the pantheon of global crops.

List examples mentioned in the article of science helping to address problems caused by palm oil production.

If you happen to mention palm oil to most people outside of Asia you are unlikely to get a particularly positive reaction. Over recent years, media coverage of palm oil has typically included images of displaced orangutan and burning, degraded tropical forests. There has been a feeling that palm oil is an evil that needs to be stopped. Indeed, in some richer countries, there have been attempts to organize consumer boycotts of palm oil products. Tanging from cosmetics to chocolate. Examples include France, the United Kingdom and Australia. But there is another story about palm oil that is much less frequently heard, especially in richer countries. This is a story about an ancient and bountiful African tree whose fruits provide a wholesome, vitamin-rich oil that feeds 2 billion to 3 billion people in 150 countries every day.

The oil palm tree has been cultivated as a source of food and fibre by people in western Africa for as much as 4,000 years and was harvested by our hunter-gatherer ancestor for tens of millennia. Palm oil is a uniquely productive crop. On a per-hectare basis, oil palm trees are 6—10 times more efficient at producing oil than temperate oilseed crops such as rapeseed (canola), soybean, olive and sunflower. The trees also have a productive life of around 30 years. Soil in oil palm plantations is rich in organic content and is less disrupted compared to temperate, annual oil crops where highly destructive annual ploughing of the soil is required.

In 2014, the total estimated global production of palm oil was almost 70 million tonnes (Mt). Over 85% is exported from Indonesia and Malaysia, mostly to India and China, where the fruit oil is used in food, including as a cooking or salad oil, and in a wide range of processed food products. If oilseed crops were to replace palm oil, it would require at least 50 million additional hectares of prime farmland just to produce the same amount of edible oil. The seed oil from palm is rich in lauric acid, a critical component in many cosmetics and cleaning products. Much of this type of palm oil is exported to Europe where it is used

in toothpaste, washing up liquids, shower gels and laundry detergents. The only viable alternative oil that is rich in lauric acid comes from coconut, but the oil yield of this plant is less than 10% of palm oil. To completely substitute coconut for palm oil would require cultivating ten times as much tropical land.

This is rarely realized by consumers who choose to use products coconut oil instead of palm oil.

Another misconception is that palm oil is overwhelmingly a "big business" crop. In fact, there are about 3 million smallholder growers, nearly all of whom farm individual family-owned plots. In Indonesia, which is the largest palm oil-producing country, smallholder plots account for the total crop area. I have recently returned from a fact-finding visit to Sarawak where we saw some of the innovative ways that local people are growing oil palm alongside other crops. Over the past year or so the pendulum of informed opinion has started to swing away from a simplistic view of palm oil as an unmitigated environmental scourge and towards a more nuanced approach that recognizes the genuine pros and cons of this bountiful tropical crop. One of the most encouraging developments has been the establishment of a reasonably robust and independent body to certify the environmental and social credentials of palm oil. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, or RSPO, has a vision to "transform the markets by making sustainable palm oil the norm". The RSPO has over 2,000 members globally that represent 40% of the palm oil industry, covering all sectors of the supply chain.

There is also an increasingly active international research effort aimed at understanding the ecological and environmental impact of oil palm compared to other habitats such as rainforests and rapeseed or soybean farms. One example of this research is a recent analysis of tropical peat soils, some of which have been targeted for oil palm cultivation. When improperly farmed these soils can release large amounts of CO2 and grow poor crops. But the analysis found some of the types of peat can readily support oil palm crops without high CO2 emissions, while others should bc left un-farmed and conserved. They conclude that rather than a blanket-ban on farming peat soils, decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis depending on the type of peat. Another study did a more rigorous life cycle assessment of oil crops, which is a measure of their overall environmental impact and found the overall ecological impact of palm oil is comparable, and sometimes superior to temperate crops. Two other studies examine the potential impact of land use and climate change on biodiversity in Borneo where a great deal of oil palm planting has occurred. The conclusions include the need to establish nature reserves in upland areas where climate change will be less severe and to improve connections between reserves and plantations with wildlife corridors.

There are undoubtedly many significant challenges facing oil palm, and further encroachment onto sensitive native forest areas should be minimized and eventually halted. But palm oil is also a uniquely efficient edible crop that is essential for food security in Africa and Asia. By working together as an international community that includes scientists, farmers, processors and consumers we aim to develop solutions to many of the problems faced by oil palm. Hopefully, this will soon enable palm oil to regain its rightful place as one of the stars in the pantheon of global crops.

Denis Murphy gives a strong argument in support of palm oil production. Write a counter-argument based on the harm that palm oil production has caused to tropical ecosystems in South- East Asia. Apply scientific language effectively in your argument.